In the fall of 2019 I received an invitation to address the

board of directors for a well-known national religious organization. Knowing

that the group was largely made up of non-scientists, I accepted the invitation

and presented a talk titled “Questions asked of a molecular biologist.” The talk was followed by a time for questions

and discussion. The presentation was not recorded, but I provide a synopsis

here.

It is a special pleasure to be able to speak to you today. I

am aware of the impressive speakers that have addressed this group,

and it is an honor to be counted among them.

My goal as a professor of molecular biology and as a

Christian believer, is not to make you comfortable, but to make you think.

Thank you for the work that you do. I pray that my words

today will be clear and will magnify our view of God. Indeed, I am convinced

that our view of God always needs magnification.

I’ve chosen this topic for my remarks today – Questions

asked of a molecular biologist. I chose this topic because of what I found to

be an unexpected and remarkable experience this past year. It was the

opportunity to speak openly and honestly with a group of biomedical science graduate

students who are spiritual seekers from many different backgrounds. Two of the

students originally approached me as a faculty member and dean, knowing of my

Christian faith even as I lead an NIH-funded molecular biology research lab and

am married with two adult children. One of the seeking students had faced a

difficult year, confronted by the deaths of loved ones. She and her colleague met

me on the sidewalk one afternoon.

“Would you ever be willing to sit down and talk about

whether there is more to life beyond the experiments we do and the data we

collect?”

My answer was simple.

“Yes” I said.

“The only rule of discussion would be that I participate as

another voice in the circle – not as teacher or professor or dean. I’ll present

my path as a seeker, and explain my Christian faith, but then listen as you

speak and share and ask questions. Maybe we can discover some common questions

that lead you to wonder about whether there is more.”

The two students immediately agreed, and quickly identified

three more students to participate. These were extremely intelligent students

from across the globe, all at my institution for PhD training in biomedical

sciences. These were students from very different backgrounds. Most had been

raised in faith traditions but had become seekers because of doubt or the

disconnection between the teachings of their faiths and the realities and

questions of their professional and personal lives. The students represented

Hindu, Muslim, Roman Catholic, Evangelical Christian, and agnostic backgrounds.

All agreed to meet monthly for an hour over almost a year. The discussion

topics emerged spontaneously after each meeting and different students led

different discussions. Often the leader of the month would post one or more

readings to spur reflection or discussion before each session.

I found that many of the topics reflected ideas and

questions related to material I had already posted at my blog,

so I commonly cross-referenced one of my essays as I provided resources for

reflection. If these kinds of topics intrigue you, I refer you to my blog as

well. In my blog I treat thoughts at the intersection of science, family, and

faith. For example, if you are curious why this professional baseball player is

holding a praying mantis on a baseball, and what that has to do with the

relationship between science and faith, you can find my discussion of the topic

here.

Although our seeking exploration covered more than a dozen

topics, I have chosen to share today four of the questions that struck me as

particularly interesting. These are topics where young scientists are

rightfully curious, and problems that skeptical trainees must confront to make

sense of a world where their personal lives and experiences are balanced with professional lives involving measurements and the reproducibility

of experiments, and ideas touching on the invisibly small molecular machines of

life.

As background, this is my church home, Autumn Ridge Church

in Rochester, Minnesota. I have been privileged to have volunteer leadership

opportunities in this large and diverse Christian congregation. I continue to

enjoy serving as a musician and I produce an Arts Series that for 13 seasons

has brought two concerts with world-class performers to Southeast Minnesota

each year.

I was raised in a church-going family that was part of a mainline denomination, but

even after baptism and first communion and confirmation, I had never come to

terms personally with the central claims of Christianity – that I constantly

fail to live up to ethical standards of my own, let alone those of a holy

and loving God, and that this God has paid a dear price to rescue me forever

from my hopeless struggle, not because I am good, but because he is good. When

I was 17 I finally understood personally the central proposition of Christianity

and made my decision to dedicate my life to God in thanks for the sacrifice of

Jesus Christ on the cross for me. This faith decision has changed everything

about how I understand the world and my place in it.

I am also a PhD molecular biologist. My BS and PhD degrees

are from the University of Wisconsin – Madison, and I did postdoctoral work at

the California Institute of Technology before beginning my career as a

professor of biochemistry and molecular biology. I have had my current research

and teaching position for 25 years.

This photo shows what I particularly love about my job – the

chance to work with brilliant young scientists from all over the world. Perhaps

it is not appreciated, but the majority of cutting-edge molecular biology that

is done to address the unknowns of how life works is done by young apprentice

scientists in their 20s. When I began my career, I was just a few years older

than my student apprentices. Now they are slightly younger than my own adult

children.

Working with extremely intelligent, skeptical, and productive

students is a prescription for staying young. Their lives are turbulent and

exciting – first partners, first jobs, first pets, first major failures and

self-doubts, first major successes, first divorces, the first illnesses and

deaths of family members, first true loneliness, first long distances from

home, first doubts about career goals.

It is exciting to be a mentor to such students.

And they find themselves asking ‘why’ questions that are

beyond the reach of the experimental science they do all day and many nights. ‘Why’

questions are every bit as important as ‘how’ questions, but science is not

designed or equipped to answer ‘why’ questions. It is the ‘why’ questions that

bring tearful students to my office to share their vulnerabilities and doubts

and fears and shame with me, not infrequently. At these ‘why’ question times I

have come to find it a privilege to listen and counsel and advise, even as the

tears can be disarming. I ask myself ‘how would I want a professional colleague

to treat one of my adult daughters at a stressful time such as this?’

It was in this context that I agreed to participate in a

discussion of hard questions asked by very smart, seeking students. In many

ways the student-requested discussion was something I had always hoped to do,

and perhaps something I will do again.

I think what made me especially comfortable with it was that

I wasn’t my idea.

So here are four of our group questions that I’ve chosen to share today.

So here are four of our group questions that I’ve chosen to share today.

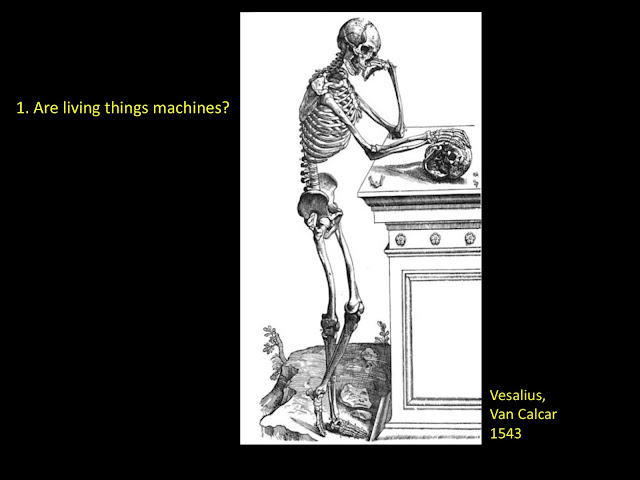

Let’s begin with the first. “Are living things machines?”

In a sense, the answer is simple, and we know that it is

“yes,” especially because of the work of Vesalius and van Calcar, as shown in

this beautiful rendering from 1543. All living things are flesh and bone, bark

and root at the macroscopic level, built from levers and pumps, sinews, meat

and blood, tissue. Recognition of our own mechanistic character by dissection was

one of the pillars of the enlightenment. Vesalius, da Vinci, Harvey all made

seminal contributions.

But I’m here to answer the question with a more fundamental

‘yes’ than Vesalius or da Vinci or Harvey could have given. I’m here to affirm

that living things, all of us, are digital machines all the way down to the

nano level.

In fact, this is the realm of nanomachinery where I work. These

nanomachines are millionths of inches small, invisible, but

still absolutely mechanistic. The DNA code molecule shown in this picture is a

mechanical ladder where the segment of rungs shown here is a millionth of an

inch long, but the three billion rungs of ladder code in each human cell add up

to 6 feet of invisibly thin double helix, packed with digital instructions

encoded as a linear hard drive – two copies of every inherited instruction, one from mom, one from

dad, needed to make another entire human identical to us.

Indeed, we are machinery all the way down to the nanodevices

that form our cells.

The idea that DNA carries all the coded recipes for all of

the nanomachines of life has always delighted and fascinated me. That’s why I

still have this 6-foot-tall poster on the wall outside my office at work. It

shows the map of the coded blueprint information, the recipe locations, for the

20,000+ recipes for all the nanomachines needed to make a human cell. The

recipes have all been sequenced now – we know the code, so we can read this book

of life and labs like mine study how the code is organized, how only some

recipes are used at any given time, and what goes wrong when recipes have

errors or are read at the wrong time and place in cells.

If we zoom in on this map, we start to see the locations of individual recipes, written into stretches of thousands of rungs of DNA ladder code, all coiled and folded and packed into volumes like a huge, complicated cookbook of recipes, organized in unexpected and perplexing ways.

If we zoom in on this map, we start to see the locations of individual recipes, written into stretches of thousands of rungs of DNA ladder code, all coiled and folded and packed into volumes like a huge, complicated cookbook of recipes, organized in unexpected and perplexing ways.

We, and all living things, are machines all the way down to

the nano scale. Here is an example of our digital code, written with the

letters G,A,T,C to substitute for the chemical rung structures of DNA.

The code

is read out by a copying machine and then a translation machine so the string

of DNA is first rendered as an RNA copy, but then interpreted by translation so

each group of three original DNA letters corresponds to one ‘bead’ on an

eventual string of amino acid beads, that will fold into the functional protein

nanomachines of life. These invisibly small proteins become the meat and bone

and goo of living things.

How cool that scientists before us figured out this genetic

code! How absolutely cool that all living things share the same code – there is

just one universal digital language shared by everything that is alive – and we

can read it! We scientists can copy and paste digital recipes and rewire cells

to do new and different things – all because we are machines all the way down

to the nano scale, and machines built from coded instructions, and coded

instructions of just a single language for all living things. In this example, the recipe code starts at

the letters “ATG” and ends at the letters “TAA” with each triplet between indicating

a different one of the 20 possible amino acid ‘beads’ forming this string that

folds automatically to form this machine that we study in our lab.

This particular machine shown in red is part of a larger

machine. We study it because when it is broken or missing, cells can grow out

of control and become cancerous tumors.

Now here is something incredibly cool. Because we can read the genetic recipes written in the DNA of different living things, we can compare these recipes! In fact, it soon became clear that all living things are built from similar recipes, and the same kinds of nanomachines are doing their things in all of us, from humans to other animals, plants, bacteria…everything.

Here I have lined up the genetic recipes for one of the

machines my lab studies in humans. The recipes for this machine are shown for

bacteria, yeast, humans, and pigs. The recipes are shown with 20 different

letters to represent the 20 different amino acids coded by the sequential

triplets of G,A,T,C DNA letters I showed earlier. If we look at the code

sequences for this nanomachine we quickly realized that the codes look similar!

We can recognize the patterns and in some places the codes for this machine are

identical in bacteria and humans! Where the codes aren’t identical, they are

often similar. This machine is quite similar, even interchangeable, across many

living things.

Not only are living things machines, but the digital codes

in living things can be compared.

This was a HUGE discovery, because it means that we don’t

have to just compare how living things look on the outside, we can actually

read the instruction blueprint for each kind of living thing and compare the

blueprints.

This is where I want to share a very important point. Without any ax to grind, scientists began comparing the digital codes in living things. Scientists did something kind of obvious – they used the kinds of comparison tools used to compare the familiar codes that we humans call languages.

Few people doubt that languages are related, and that

languages have descended from common ancestors. We see this in the similarities

of certain languages, and we can recognize the sounds of words in other

languages descended from common ancestors.

In fact, languages evolve. They change over time. As

groups of people become separated, their languages drift and become different

enough that different language groups can no longer communicate.

Here is a common tree diagram depicting the relationship between languages. The common ancestor languages can be deduced. I’ve never heard anyone claim that all languages were created at once in their present forms. It is self-evident from the codes that languages descended from common ancestors over long times.

Charles Darwin studied the macroscopic external appearance

of plants and animals and deduced common ancestry, proposing an evolutionary

theory for the relationship between all living things. Darwin did this based

only on what he saw, kind of like trying to propose relationships between

languages based only on how they sound.

How amazing was it then when, more than a century later,

scientists realized they could compare the DNA codes inside of living things.

This is like comparing languages as written codes rather than just by listening

to the sounds of the words.

What became instantly clear is shown here. The same tools

that show relationships between languages through common ancestors forming a

language ‘tree’ revealed an absolutely analogous ‘tree of life.’ The best and

most obvious explanation for this tree is exactly the same explanation as for the

language tree – living things have evolved over time from common ancestors.

This wasn’t an evil scheme to destroy religious faith – it

was simply the realization that Darwin’s insight based on appearances had been

shown to be correct by reading the digital codes built into every living thing.

Amazing.

So are living things machines? Yes. From what we can see right down to the

nanoscale, they are all machinery – we are all machinery. And the digital

coding of life makes it absolutely obvious that all living things are related

to each other – and since the relationship looks just like the relationship

between languages that have evolved from each other over long periods of time

with change and separation, evolution over a long period of time is the obvious

logical conclusion of this discovery that living things are machines based on

digital code.

This "yes" conclusion prompted an obvious question in our

discussion group. If living things are material, and the enlightenment moved us

away from animism to a mechanistic view of life, is there any room left for the

concept of a soul – an aspect of life that is beyond the mechanical – an aspect

that might commune with a higher power, a creator if there is one – an aspect

of life that lies on the ‘why’ dimension – an aspect of life that might

transcend the mechanical and outlive the machinery?

What is a soul?

What a great question. I have blogged about this question in the past, so we discussed a possible direction for thinking about the soul. My argument

has been based on the concept of emergent

properties – properties of large and complex systems that are not readily

explained by the properties of the component parts.

My analogy relates to the concept of ant colony behavior

that isn’t predictable by studying individual ants. Ants are cool, but…

Ant colonies do lots of things that individual ants do not.

These colonial behaviors are kinds of emergent properties observed only when

hundreds or thousands of ants work together and we start to realize that there

is a kind of ant colony “organism” that we only understand when we grasp that we can't understand the purpose of an

individual ant, its ‘why,’ until we see it in context.

There is a possible analogy that gets us to the soul. It is the analogy between ant/colony and neuron/brain. It is entirely plausible that the 100 billion neuron cells of the human brain are the ants and the brain is the colony, replete with emergent properties unpredicted by the characteristics of neurons. These are properties like self-awareness, consciousness, selflessness, love, and the longing for connection to a purpose and the sensed yearning for the love of a creator.

I think this is such an interesting idea.

And it has fascinating implications that our group

discussed.

First, if the soul is an emergent property of a complex

brain, we must confront the fact that humans are not the only animals with

complex brains. Are all creatures machines, but only humans have brains

large enough to spawn emergent souls that are loved by a creator God and can

commune with that God beyond this life? What if the different brains of all

kinds of creatures generate different kinds of souls that are loved and find

transcendence with such a God?

Wow.

Second, if the soul is an emergent property of a complex

brain, what happens when that brain dies? An ant colony has no emergent

properties when all individual ants are dead. There is no immortal emergent

property of an ant colony except perhaps our memory that such a colony once

existed. What of a soul that is an emergent property of a living brain? When

the neurons cease to function, what of that soul? Here we discussed the notion

of reincarnation, or in Christian terms, resurrection. If the soul is an

emergent property of a complex brain, the soul is immortal if that physical brain

can somehow be made immortal by resurrection – re-integration – recreation. If that brain is physically rebuilt in a manner that is timeless, a

timeless soul re-emerges.

So, though by no means a trivial idea, the fact that living things are machines does not kill the idea that a transcendent soul could emerge from a complex mechanical brain. Such a soul is a way to understand the aspects of human life whose aesthetics provide ‘why’ answers in a mechanical universe that otherwise lacks them. As I have discussed in a previous post the idea that answers to ‘why’ questions are totally fair and desirable even though such answers are off limits for experimental science.

Our discussion group was made up of students trained in

molecular biology, though each was studying different fields and questions. The

group did find itself discussing the ethics of application of technology to the

mechanism of living things. Since living things are machines, and since we

increasingly understand that machinery, we are learning to engineer it. In some

ways this is the story of medicine, and in some ways it is also the ancient

story of selective breeding. The latter is just genetic engineering done in

slow motion and without mechanistic insight.

But what of newer and faster techniques that allow us to

engineer the digital blueprints present in the DNA of all living cells? As we

change this blueprint information, we change the character of the cell. As that

cell divides, we have the potential to change the character of the resulting

organism – or even to make new kinds of organisms. Is this something to worry

about?

The reason this is on our minds is the discovery and optimization of a wonderful and unexpected technology found buried within the deep inner workings of bacteria. This is an ideal example of a principle that I try to communicate to the lay public every chance I can – the revolutionary discoveries that change medicine for humans almost exclusively come from studies driven by curious scientists simply interested in how living things work, very often without any obvious connection to human health. This is one of the reasons why it is so important to promote and support the work of curious scientists – we simply don’t know what is going to turn out to be important for human medicine.

This is also exactly the case for the discovery of the CRISPR/Cas9 machinery hidden in bacteria.

The reason this is on our minds is the discovery and optimization of a wonderful and unexpected technology found buried within the deep inner workings of bacteria. This is an ideal example of a principle that I try to communicate to the lay public every chance I can – the revolutionary discoveries that change medicine for humans almost exclusively come from studies driven by curious scientists simply interested in how living things work, very often without any obvious connection to human health. This is one of the reasons why it is so important to promote and support the work of curious scientists – we simply don’t know what is going to turn out to be important for human medicine.

This is also exactly the case for the discovery of the CRISPR/Cas9 machinery hidden in bacteria.

We simply had no idea that bacteria carry their own immune systems, helping them fight off their own parasites!

Who knew?? We think of bacteria being the parasites, but they themselves have been in an ancient

battle with their own parasitic viruses (called bacteriophages) and dangerous

parasitic mobile DNA molecules.

The name of the CRISPR system (an acronym standing for clustered regularly interspaced short

palindromic repeats) illustrates the accidental way in which the system was

discovered. The molecular nanomachinery that performs the immune functions was

not discovered first. Rather, it was peculiar features of the genetic blueprint

instructions for CRISPR in the bacterial DNA that caught the attention of DNA

sequencing bacteriologists before they had the slightest ideas what was encoded

by these DNA patterns. Remarkably, bacteria with CRISPR systems preserve a

digital record of samples of the DNA codes of invading parasites so this

library of code specimens is ready in the DNA blueprint of the bacterium

itself, allowing every piece of DNA to be checked against this library, for

safety.

Amazing? It is like

a facial recognition system to destroy anyone depicted on a ’10 most wanted’

poster.

To appreciate this natural and unexpected bacterial

technology and how it has been re-engineered by clever scientists, consider

another analogy that I used in our group’s discussion of the ethics of

CRISPR/Cas9. This analogy is a simple zipper.

The double-stranded DNA in cells is a molecular ladder

twisted into a spiral, and it is in some ways like a zipper. The analogy is not

perfect, but it is surprisingly good. We just have to remember that unlike the

identical teeth in the zippers in our clothes, DNA zipper teeth come in 4

shapes, and the DNA zipper can’t zip unless the teeth match in a complementary way – DNA

is a smart zipper.

Amazingly, the CRISPR system is like the single red zipper strand shown here without a partner. Let’s imagine that in this room full of people wearing clothes with zippers, each person’s zipper is slightly different as far as the sequence of the zipper teeth. If one of us is a dangerous criminal, how might we be detected? How about a zipper ID test? Let’s say we have a record of the order of teeth on one section of the criminal’s zipper, and it is available as this single red probe zipper. One way to find the criminal is to allow this single red probe zipper to test for matches with all the zippers on the clothes of the people in this room.

Seems crazy, but that is exactly how the CRISPR system

works.

The CRISPR system has a zipper tab that can start probing almost anywhere along any zipper. Prying into the target zipper, it inserts its red single zipper and tests for a match to the potential criminal sequence by zipping.

The CRISPR system has a zipper tab that can start probing almost anywhere along any zipper. Prying into the target zipper, it inserts its red single zipper and tests for a match to the potential criminal sequence by zipping.

Most zipper teeth won’t match and the CRISPR system then disengages

harmlessly. However, if a perfect match is found all the way along the

teeth of the red single probe zipper, the fully-zipped product triggers a

clever machine that physically cuts the target zipper so it can no longer close.

[Reflect for a moment on the implication in the analogy for

the criminal in this room if the recognized and destroyed zipper is the one

that keeps the criminal’s pants closed.]

Here is a molecular view of the actual CRISPR/Cas9 machinery,

also less than a millionth of an inch in size. I colored it so the red single

zipper is red, and the grey target zipper whose tooth order is being checked is

grey. In this picture, the green stuff is the protein that acts as both the

zipper tab that is inserted in the target zipper to do the checking, and the

scissors that are activated if a perfect match is found.

Our discussion group, being made up of molecular biologists,

was somewhat familiar with this molecular machine, so we reviewed it as well as

its unlikely discovery within bacteria, and its subsequent engineering. This

engineering means that the little machines can now be engineered with whatever

red single zipper tooth sequence we want, so the machines will scan and cut

target DNA zippers only where we wish.

Cutting a target zipper DNA in a living cell has the

interesting effect of triggering the cell to undertake a haphazard repair

attempt that results in a repaired zipper with a kind of scar that has a slightly different sequence of

teeth than the original, often destroying the meaning of the code. These errors

can destroy the genetic recipe encoded by the target zipper sequence, allowing

scientists to edit (crudely for now) the recipe list.

One of the big challenges is getting the red single zipper

inside of cells where it can do its job. That’s one of the things we work on in

our lab, but that is also a different story…

So, the question our group asked was whether we should be

alarmed by the availability of this CRISPR technology, stolen from bacteria,

and engineered to alter gene recipes in any organism, including humans.

The group reflected on the fact that this kind of gene

editing might be applied in two general ways.

If the gene edit is made in a normal body cell (a “somatic” cell) of an organism such as a human patient, the change stays in that patient and is not passed along to offspring.

If, however, doctors or scientists figure out how to make the gene change in one of the eggs or sperm ( the ‘germ cells’) of a human patient, their DNA is then included in the new fertilized embryo to create the genetic recipes for the baby. In fact, every single one of the trillions of cells in the resulting baby would inherit the same gene change made by CRISPR in the egg or sperm. Such technology has powerful implications that have already triggered ill-considered attempts to alter eggs so the resulting babies have a designed gene change in every cell. These changes would then be inherited by their offspring, and the human race altered a little bit by the effort.

Such “germline” gene editing is currently illegal, and our

group agreed that it is premature to consider the idea of “medicine” that

alters families now and in perpetuity. We’re just not smart enough to

understand the implications of this kind of medicine.

On the other hand, editing DNA within the somatic cells of

an individual patient is not nearly as ominous, as the effects are limited to

that individual.

We concluded that we should not be alarmed by the

availability of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology. It is a tool, neither good

nor bad. We should explain the tool to the public, and help guide ethical use

of the tool. For now, that means limiting its use to the editing of somatic

cells where it may be of use as a new kind of precision medicine in some

patients.

This then brings us to a fourth discussion topic that I found particularly interesting.

This then brings us to a fourth discussion topic that I found particularly interesting.

The students asked why so many Christians are so

frightened by the ideas of an ancient earth and evolutionary origins. As

scientists, we wanted to appreciate the source of these fears and concerns in

order to improve our dialog with Christian people who feel threatened by these

very important scientific concepts. We also wanted to explore whether there is

something about Christianity that is inconsistent with the findings of science.

Are Christianity and science complementary ways of

discovering and understanding the same truth, or are they inconsistent?

Those familiar with my blog know that I’ve posted several things about this issue before – here, here, here, and this video.

As we discussed with our discussion group, I believe the

central issue comes down to this illustration and how we choose to understand

the written documents of Judaism and Christianity, what we call the Old and New

Testaments of the Bible. Christians derive their understanding of God from

these documents, and Evangelical Christians believe that the documents are

worth studying. The question is ‘in what sense are these documents true?’ Some

Christians see the biblical documents as if they were a textbook, all written

in one coherent format, as if by one author, all for one purpose. I show here one

of my favorite textbooks, Richard Feynman’s Lectures

on Physics, as an example. Textbooks are one kind of literature, and we

understand them by studying them in a certain way.

I have argued that the Bible is not a textbook. It

is much more interesting than that. The Bible is a scrapbook.

Scrapbooks (at least those like my own scrapbook, shown here) are full of

mysteries and surprises and puzzles, contradictions, delights.

The Bible is a scrapbook and it does not reveal many ‘how’s (as it would if it were a textbook), but it does reveal many ‘why’s. This makes

it a particularly unique and important collection of documents reflecting the

contributions of dozens of authors over centuries of time.

So, part of the fear of some Christians about scientific

evidence for an ancient earth and evolutionary origins can be traced to the

desire to read and understand the Bible as a textbook.

We discussed another likely contributor to discomfort about

an ancient earth and evolutionary origins – the truth of these concepts tends

to reduce the special importance of humans.

This is a problem because we like to be especially

important.

I like this quote from pastor Rick Warren. Rick makes the

point that we like to think of the universe from the reference frame of…us. The

Bible meets us in this reference frame, but that doesn’t mean that it is the

ultimate reference frame – it is simply the only reference frame our tiny minds

can comprehend.

It hasn’t taken long for modern instruments descended from

Galileo’s original telescope to remind us that our place in the universe is

insignificant, as is the amount of time we have been living here.

Sobering but true.

Our discussion group thus decided that another reason some

chafe against an ancient earth and evolutionary origins is that we find

ourselves no longer the main event, the stars of the show. We are told in the

Bible that we humans are specially loved and that have been purchased by God

through an expensive and mysterious sacrifice.

But this doesn’t mean that we are unique. It doesn’t mean

that God has no other love stories in other places, times, or universes.

This image of earth from beyond Saturn might please Galileo,

who was the first to see moons circling Jupiter, reminding us that the earth is

not the center of everything.

In fact, the earth is the center of very little.

As I have posted, our place in the universe is unimaginably small. That a powerful and creative God is at all mindful of us is the miracle. The size of our planet relative to the size of known universe is on the same order as the size of a grain of sand relative to the size of the entire planet earth. On that massive scale the single sand grain is too small to matter – isn’t it?

Our group discussed my post that we humans may dislike the

idea of evolutionary origins because it destroys the sense that human history

is a significant part of the history of the universe.

It isn’t. The 10,000 years of recorded human civilization

are to the age of the universe as the last two seconds of time are to the

previous month. Inconsequential. Insignificant.

In the world we are discovering through science, the space

and time of humanity lose their prime status. Rather than being obvious that a

loving God must attend to us, it becomes unfathomably remarkable that we merit

the least notice in the blink of time that we have occupied this dark corner of

what may be just one universe of a multiverse.

No wonder some are discomforted by the ideas of an ancient

earth and evolutionary origins. These ideas force us to rethink the Bible as

textbook, requiring more homework to unpack the purpose of the biblical scrapbook.

These ideas also force us to confront our insignificance.

Apparently the only reason our human story is important is because

God says it is.

Our group discussed how these are not particularly new

ideas, but they have been rediscovered over and over in history. This is one of

the great reasons to study history and literature – to realize that we may be re-fighting

intellectual battles that were already won by thinkers like Augustine and Galileo

centuries ago. In his The Language of God,

molecular biologist Francis Collins calls these the Lessons of Galileo.

I smile audaciously to then contribute my own quotation along the same

line, and it sums up what our discussion group concluded in considering an

ancient earth and evolutionary origins.

So, we come to the conclusion of this story of a remarkable

group of seeking students and their willingness to ask important questions of a

molecular biologist.

They knew that I have lived my live as a professional

scientist and as a person of faith. They wanted some insight into how that combination

can coexist. By the end of our sessions together, I had shared my own path to

Christian faith, and I had tried to be honest and vulnerable about the feelings

of guilt and loneliness that led me to investigate, and eventually accept, the

claims of Jesus Christ.

We then talked about more than a dozen topics, including the

four summarized here.

Thank you so much for your attention. Let’s have some

discussion!

1.14.20

A reader comments:

I enjoyed reading your presentation - rigorous discussion around very complex topics. I am not a young earth proponent, but I do have one question: What is the difference between the DNA building blocks evolving over millions of years, like languages, into different species versus God using those building blocks to design life in more real time? Does the DNA profile look the same either way? Is the only difference the amount of time God used to complete the task (allowing / guiding macro evolution vs. a more "fast path" or micro evolution approach)?

Response:

Great question.

I use the language analogy to get us thinking. The biblical story of Babel (Genesis 11:1-9) might suggest that God created all the different languages at once by confusing the speakers of one original language with a single act. That’s what we would deduce if the Bible is a textbook. If the Bible is a scrapbook that includes stories and mythology meant to help explain things that are hard to explain (like different languages), then we are open to the possibility that the real origin of languages is different from the Babel story, or perhaps better stated, that the Babel story doesn’t likely explain the different languages we experience today. By studying the languages of today, we see that they are related in a way that points to common ancestry, and we can make diagrams that illustrate the likely family tree. As we watch language evolution we see that it is slow. It therefore seems more reasonable to explain the family tree of languages as being the result of a slow process of evolution, based on the principle that it is simplest to assume that processes currently observed are generally similar to processes that took place in the past. That means language evolution has been taking place over many thousands of years. Could God have created all languages in their current form very quickly, and then just created the appearance of a family tree of relationships because that is beautiful? Sure. God can do almost anything except be untrue to himself. It is just easier to understand languages as having arisen by gradual processes. The only reason not to believe that is if we insist that the Babel story is taken as a textbook account and applied universally to all languages.

So, the same goes for the genetic relationships between organisms. Could God have quickly created all the kinds of organisms using a process that created the appearance of the genetic family tree that we see by gene sequencing, including genetic parasites and broken genes? Of course he could have. He can do almost anything. However, based on what we see going on now, and processes and the measured pace of genetic changes, and based on the assumption that current processes are generally a reasonable model for past processes (the simplest assumption of science where miracles aren’t invoked), the time to build the current genetic tree of life would be thousands of millions of years. This doesn’t mean that remarkable things like asteroid impacts haven’t occurred in earth history, so unusual events are allowed. My argument is that the simplest explanation for the tree of life, as for the tree of languages, is a long, slow process that appears random even if it is, in fact guided by God. Simplest explanations win in science. The only reason to invoke the hand of God in a sudden process that just imitates the slow process is insistence on understanding the Bible as if it were a textbook.

I’m quite convinced that the writers of the Bible never claim that it is a textbook (!), or that it should be understood as a homogeneous and uniform document containing a single style of literature. That’s why it doesn’t bother me at all to choose the simpler explanation that is more consistent with what we observe with our eyes and experiments, rather than reverting to seeing the world through the lens of a textbook reading of the Bible.

After all, it was insistence on a textbook reading of the Bible that suggested a geocentric universe, and that got Galileo in trouble when he found moons orbiting Jupiter rather than earth. My argument is that we long-ago learned that the textbook view of the Bible is not particularly valuable in astronomy and cosmology. We all pretty much understand that now.

It is taking longer to realize that the same is true for languages…and biology ☺.

The reader comments again:

That is a very helpful explanation, and I don't necessarily disagree with it. I am not convinced, however, that just because one thinks there was miraculous intervention (i.e God sped up the process from what we observe today) it means that one reads the Bible as a textbook. I don't make that connection. I think the overwhelming scrapbook story of Scripture is that God intervened. He certainly intervened in the incarnation. He could have also intervened in creation - and in fact did at some point in the process. "In the beginning God (vs. chance) created the heavens and the earth." It seems to me we can have differing views of how he created and over what period of time without thinking of Scripture as a textbook. Thoughts?

Response:

Yup. Good thoughts.

I would just make some comments about the concept of God “intervening.” Though it is debated by theologians, my personal conviction is that God exists outside of time, and created time for his purposes without needing to exist within it. This is analogous to a playwright or composer creating an artistic product in the dimensions of her own existence. While the actual performance of the piece and its characters are trapped in time and space, the creator is not. Because we are creatures of the time dimension (akin to characters in the play), we have no real ability to fathom what the existence of the playwright (outside of time) is like. We are trapped in time and can only think about timelessness by analogy. My sense that God is timeless is based on hints from the Bible, and my instinct that God is master of everything, so of time as well. I could be wrong.

The reason that prior paragraph matters is that, if it is true, it means that God has never ‘intervened’ in the sense of inserting himself into a place or plot where he wasn’t previously involved. It’s like saying that the playwright became involved in her play only here and there. That doesn’t make any sense because the playwright is responsible for the entire play from conception to crafting of plot to conclusion. The playwright might choose to write herself into the play as a character here and there, so both audience and other characters would get to know her character, and she might even create plot lines where her actions in time have dramatic and real consequences for the other characters in the play. I would not say that this would be intervention. She wrote the whole play and just chose to enter the plot as a character here or there. The whole play was written knowing of those plot twists.

So I see God as having written into the fabric of time and space and what we perceive as random chance the plot and the story, right from what we see as the start, right through to what we will see as the end. We can’t conceive it because we are creatures of time. He has accomplished this to allow for what we perceive to be free will and he knew the outcome before setting the story in motion. Indeed, that is the most encouraging thing about this universe – that God told/is telling/will tell a beautiful story well worth telling, though we see it incompletely from the perspective of time.

Now as to God being able to manipulate time for his purposes, obviously from my comments above, he can do this if it suits him. I am more concerned in my advocacy for science and Christianity with the issue of credibility. This was the point of the slide with the quote from Augustine in my talk. If we stubbornly cling to certain textbook interpretations of biblical treatments of science and cosmology and astronomy and biology and other areas that the ancient authors could not address with any authority or insight, we risk discrediting ourselves as not having a message worth hearing on matters of faith and salvation. The world is suspicious that they will need to deny the implications of objective observation if they want to accept the Gospel. They do not. I think the “foolishness” of the message of the cross for those who are perishing (Paul’s first letter to the church at Corinth, 1:18) has nothing to do with Christians needing to ignore scientific evidence staring them in the face, it has to do with the paradox of losing one’s life to gain it.

By wrapping Christianity in an anti-intellectual package, we create an unnecessary obstacle, particularly in a city like ours. I think this is one of the central discussions for Christian leaders here over the coming years.

I am about removing obstacles.

1.14.20

A reader comments:

I enjoyed reading your presentation - rigorous discussion around very complex topics. I am not a young earth proponent, but I do have one question: What is the difference between the DNA building blocks evolving over millions of years, like languages, into different species versus God using those building blocks to design life in more real time? Does the DNA profile look the same either way? Is the only difference the amount of time God used to complete the task (allowing / guiding macro evolution vs. a more "fast path" or micro evolution approach)?

Response:

Great question.

I use the language analogy to get us thinking. The biblical story of Babel (Genesis 11:1-9) might suggest that God created all the different languages at once by confusing the speakers of one original language with a single act. That’s what we would deduce if the Bible is a textbook. If the Bible is a scrapbook that includes stories and mythology meant to help explain things that are hard to explain (like different languages), then we are open to the possibility that the real origin of languages is different from the Babel story, or perhaps better stated, that the Babel story doesn’t likely explain the different languages we experience today. By studying the languages of today, we see that they are related in a way that points to common ancestry, and we can make diagrams that illustrate the likely family tree. As we watch language evolution we see that it is slow. It therefore seems more reasonable to explain the family tree of languages as being the result of a slow process of evolution, based on the principle that it is simplest to assume that processes currently observed are generally similar to processes that took place in the past. That means language evolution has been taking place over many thousands of years. Could God have created all languages in their current form very quickly, and then just created the appearance of a family tree of relationships because that is beautiful? Sure. God can do almost anything except be untrue to himself. It is just easier to understand languages as having arisen by gradual processes. The only reason not to believe that is if we insist that the Babel story is taken as a textbook account and applied universally to all languages.

So, the same goes for the genetic relationships between organisms. Could God have quickly created all the kinds of organisms using a process that created the appearance of the genetic family tree that we see by gene sequencing, including genetic parasites and broken genes? Of course he could have. He can do almost anything. However, based on what we see going on now, and processes and the measured pace of genetic changes, and based on the assumption that current processes are generally a reasonable model for past processes (the simplest assumption of science where miracles aren’t invoked), the time to build the current genetic tree of life would be thousands of millions of years. This doesn’t mean that remarkable things like asteroid impacts haven’t occurred in earth history, so unusual events are allowed. My argument is that the simplest explanation for the tree of life, as for the tree of languages, is a long, slow process that appears random even if it is, in fact guided by God. Simplest explanations win in science. The only reason to invoke the hand of God in a sudden process that just imitates the slow process is insistence on understanding the Bible as if it were a textbook.

I’m quite convinced that the writers of the Bible never claim that it is a textbook (!), or that it should be understood as a homogeneous and uniform document containing a single style of literature. That’s why it doesn’t bother me at all to choose the simpler explanation that is more consistent with what we observe with our eyes and experiments, rather than reverting to seeing the world through the lens of a textbook reading of the Bible.

After all, it was insistence on a textbook reading of the Bible that suggested a geocentric universe, and that got Galileo in trouble when he found moons orbiting Jupiter rather than earth. My argument is that we long-ago learned that the textbook view of the Bible is not particularly valuable in astronomy and cosmology. We all pretty much understand that now.

It is taking longer to realize that the same is true for languages…and biology ☺.

The reader comments again:

That is a very helpful explanation, and I don't necessarily disagree with it. I am not convinced, however, that just because one thinks there was miraculous intervention (i.e God sped up the process from what we observe today) it means that one reads the Bible as a textbook. I don't make that connection. I think the overwhelming scrapbook story of Scripture is that God intervened. He certainly intervened in the incarnation. He could have also intervened in creation - and in fact did at some point in the process. "In the beginning God (vs. chance) created the heavens and the earth." It seems to me we can have differing views of how he created and over what period of time without thinking of Scripture as a textbook. Thoughts?

Response:

Yup. Good thoughts.

I would just make some comments about the concept of God “intervening.” Though it is debated by theologians, my personal conviction is that God exists outside of time, and created time for his purposes without needing to exist within it. This is analogous to a playwright or composer creating an artistic product in the dimensions of her own existence. While the actual performance of the piece and its characters are trapped in time and space, the creator is not. Because we are creatures of the time dimension (akin to characters in the play), we have no real ability to fathom what the existence of the playwright (outside of time) is like. We are trapped in time and can only think about timelessness by analogy. My sense that God is timeless is based on hints from the Bible, and my instinct that God is master of everything, so of time as well. I could be wrong.

The reason that prior paragraph matters is that, if it is true, it means that God has never ‘intervened’ in the sense of inserting himself into a place or plot where he wasn’t previously involved. It’s like saying that the playwright became involved in her play only here and there. That doesn’t make any sense because the playwright is responsible for the entire play from conception to crafting of plot to conclusion. The playwright might choose to write herself into the play as a character here and there, so both audience and other characters would get to know her character, and she might even create plot lines where her actions in time have dramatic and real consequences for the other characters in the play. I would not say that this would be intervention. She wrote the whole play and just chose to enter the plot as a character here or there. The whole play was written knowing of those plot twists.

So I see God as having written into the fabric of time and space and what we perceive as random chance the plot and the story, right from what we see as the start, right through to what we will see as the end. We can’t conceive it because we are creatures of time. He has accomplished this to allow for what we perceive to be free will and he knew the outcome before setting the story in motion. Indeed, that is the most encouraging thing about this universe – that God told/is telling/will tell a beautiful story well worth telling, though we see it incompletely from the perspective of time.

Now as to God being able to manipulate time for his purposes, obviously from my comments above, he can do this if it suits him. I am more concerned in my advocacy for science and Christianity with the issue of credibility. This was the point of the slide with the quote from Augustine in my talk. If we stubbornly cling to certain textbook interpretations of biblical treatments of science and cosmology and astronomy and biology and other areas that the ancient authors could not address with any authority or insight, we risk discrediting ourselves as not having a message worth hearing on matters of faith and salvation. The world is suspicious that they will need to deny the implications of objective observation if they want to accept the Gospel. They do not. I think the “foolishness” of the message of the cross for those who are perishing (Paul’s first letter to the church at Corinth, 1:18) has nothing to do with Christians needing to ignore scientific evidence staring them in the face, it has to do with the paradox of losing one’s life to gain it.

By wrapping Christianity in an anti-intellectual package, we create an unnecessary obstacle, particularly in a city like ours. I think this is one of the central discussions for Christian leaders here over the coming years.

I am about removing obstacles.